Virginia Woolf famously wrote a speech, which she later

turned into a short book, about the importance for a writer of having a ‘room

of one’s own’. In this particular case, Woolf’s focus was on female writers at

a time where women in Britain were just struggling towards greater levels of

emancipation and Woolf herself was seen as a kind of vanguard, being a women of

independence and great vision, as her works of fiction continue to lay

testament to. In the book ‘A Room of One’s Own’ Woolf addresses the question of

how women can venture into a writing career, and her view is that without

economic and physical freedom such a hope is illusory at best. It is an

insightful point. Economic and physical freedom remain a significant issue for

women around the world even today, and in many cases for women economic freedom

beyond the level of dire poverty remains an illusory hope. Freedom from

oppression, freedom from physical or sexual violence, for the majority of women

remains an aspiration though in some areas we have, perhaps, made a little

progress. It is only, sometimes, by reading a treatise so old (it was written

in 1928) that we come to realise how little has really changed. A Room of One’s

Own is a great, short, feminist work that elucidates many of the problems for

women in achieving their aspirations in life. Like all of Woolf’s work, it is

not an easy read, her writing is

simultaneously dense and nebulous, but it is definitely a worthwhile one.

But this blog is not about feminism, but rather why that work

has been on my mind for the last couple of weeks. I have been in the process of

creating a room of my own, a writing and reading room. I have not done this

without help, I should point out, in fact my husband has been a driving force

in this transformation and I’ve been very grateful for the considerable effort

he’s put into achieving this goal. How it happened is this: until recently I’d

been writing in the dining room. In the dining room we had a lovely oak table,

eight seater, which took up the bulk of the room. The chairs are extremely

uncomfortable. There was also a matching sideboard, a tall bookcase and loads

and loads of junk. You see, we didn’t use the dining room very often. Mostly we

eat at the kitchen table, which seats six (but extends to eight) or in the

living room, and occasionally, when we have visitors, we will tidy the dining

room and use the table. This happens, at best, 2 or 3 times a year. Most of the

rest of the time the dining room is shut away or I am shut away in it, feeling

like an interloper.

For a long time now, I have dreamed of a quiet room filled

with books. My books, until recently, were stored in communal areas: the

hallway, the landing. They were double stacked, so only half of them were on

view at any time and often the books in the back row were forgotten. I dreamed

of a room with rows and rows of shelves stuffed with books, and comfy chairs

for sitting in and reading at, and blankets for warmth, and soft lighting and

no TV and no technology, except for my laptop of course which I could use for

writing. There is something extremely attractive about silence, to me. The idea

of a quiet room, forgetting the books and the comfy chairs and all those

trappings, somewhere I can go and think and be at peace, makes me feel comforted.

I am quite adept at drowning out noise: my workplace is noisy, my train

journeys equally so, and I have learned that in order to think I have to be

able to fade that noise into the background. I am not always successful. Yet,

still, a quiet room to call my own is like my safe harbour in a storm. It is

something I need, but have never really had.

Recently we’ve started talking about this more seriously,

perhaps because I am making a much more concerted effort to bring writing into

my daily routine. The dining room was okay, but not a particularly effective

space for writing. I know environment shouldn’t be hugely important, yet I

think it is. Creative a space which is conducive to your writing, I think, is

an essential part of the journey. Or if not creating, discovering. For some

writers maybe a crowded cafe will be the right space, or a library with the

right kind of ambiance (I am thinking, here, of the lovely gothic reading room

in the John Rylands library), or maybe somewhere green with a river flowing and

a slowly decaying wooden bench.

Recently we’ve started talking about this more seriously,

perhaps because I am making a much more concerted effort to bring writing into

my daily routine. The dining room was okay, but not a particularly effective

space for writing. I know environment shouldn’t be hugely important, yet I

think it is. Creative a space which is conducive to your writing, I think, is

an essential part of the journey. Or if not creating, discovering. For some

writers maybe a crowded cafe will be the right space, or a library with the

right kind of ambiance (I am thinking, here, of the lovely gothic reading room

in the John Rylands library), or maybe somewhere green with a river flowing and

a slowly decaying wooden bench.

For me, converting one room in the house into a space in

which I can write and read and think quietly is a boon. We finally committed to

this a couple of weeks ago when, quite by accident, we discovered a typewriter

in an antiques shop and, at £9.50, we just had

to get it. I love typewriters, I’ve wanted one for a long time. My typewriter

is an Olivetti Dora portable typewriter and it’s great. What’s more, kids love

it. Both my kids and kids that have visited have spent an age tapping away at

its keys. Then I found a wonderful writing bureau for sale, secondhand, on

Gumtree. I used to have a writing bureau when I was a child, and I’d loved it.

I’d spent hours at that desk doing my homework or writing or reading the old

set of Australian encyclopaedias my Mum and Dad had brought back with them

which were stashed in the glass fronted shelves at the bottom of the bureau. I

knew that my writing desk had to be a bureau. We were lucky to pick up the one

we did; it isn’t in perfect condition, there is damage to the edges and the

leather rest needs replacing and there is some bleaching to the wood, but to me

it is perfect. It has been loved, used, abused a little perhaps. It has

character, it has stories. The lady who was selling the bureau was doing so

reluctantly and I wish I could show her, already, how much I love it, how much

it means to me. It made me realise that mostly when we have bought furniture I

haven’t cared too much about it, but this piece of furniture is already special

to me.

For me, converting one room in the house into a space in

which I can write and read and think quietly is a boon. We finally committed to

this a couple of weeks ago when, quite by accident, we discovered a typewriter

in an antiques shop and, at £9.50, we just had

to get it. I love typewriters, I’ve wanted one for a long time. My typewriter

is an Olivetti Dora portable typewriter and it’s great. What’s more, kids love

it. Both my kids and kids that have visited have spent an age tapping away at

its keys. Then I found a wonderful writing bureau for sale, secondhand, on

Gumtree. I used to have a writing bureau when I was a child, and I’d loved it.

I’d spent hours at that desk doing my homework or writing or reading the old

set of Australian encyclopaedias my Mum and Dad had brought back with them

which were stashed in the glass fronted shelves at the bottom of the bureau. I

knew that my writing desk had to be a bureau. We were lucky to pick up the one

we did; it isn’t in perfect condition, there is damage to the edges and the

leather rest needs replacing and there is some bleaching to the wood, but to me

it is perfect. It has been loved, used, abused a little perhaps. It has

character, it has stories. The lady who was selling the bureau was doing so

reluctantly and I wish I could show her, already, how much I love it, how much

it means to me. It made me realise that mostly when we have bought furniture I

haven’t cared too much about it, but this piece of furniture is already special

to me.

Then one evening I came home and my husband had removed the

dining table from the room and the next thing I know he is demanding to know

what kinds of shelves I want putting up and suddenly we’re off to Ikea and a

couple of days later I have a wall full of shelves just waiting to be filled

with books. That’s when the hard work really began. Moving and organising books

is always a trial as this blog expresses so neatly, especially when you have a very large book collection, as I do. Book moving

day looked like this:

(and that’s not all my books. Agh!). And after a day’s worth

of trial and effort, of sorting and re-sorting and bending and lifting and

carrying we discovered there weren’t enough shelves, so my husband went and got

some more and we ended up with this:

A lot better, isn’t it? Everyone loves the new room. We

still need to get some comfy chairs and a rug would be nice and some little

side tables that we can use to perch a glass of wine on and a Scrabble board.

But we can take our time over that. For now it is just wonderful to have a

nice, quiet, peaceful room. Right now I am sitting at my writing bureau typing

away and all I can hear is the whirring of the hard drive and the sweet

chirping of the birds outside and my husband vaguely prowling around the house

looking for things to do, and it is blissful.

This got me thinking about the writing rooms of other

writers. Here are some interesting examples:

Proust’s

‘soundproofed’ room

Proust famously lined his writing room with cork to limit

the noise, shuttered the windows and drew the blinds. A sickly man who rarely

left his room, instead he focused his attention on his epic exploration of

memory and time (which I will never, ever finish). This picture is a replica of Proust’s writing

room from the Musée Carnavalet in

Paris.

Roald Dahl’s shed

Roald Dahl’s famed shed in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

is now part of a museum dedicated to the art of storytelling. Dahl wrote his

wonderful children’s novels here. In some parts of London, this would be a ‘house’

retailing for something in the region of £250,000. It’s also gorgeous. Rumour

has it that no one was allowed in the hut, and no one was allowed to clean, but

if that was true how is it that we have pictures of Dahl in his hut? Curious.

Virginia Woolf’s room

of her own

If you read Virginia Woolf’s excellent diaries, she talks a

lot about her house at Rodmell, Sussex, from which she can walk out into the country,

along the River Ouse, and at which she had the ‘room of her own’, a little

writing lodge in the garden, where she produced most of her most famous works.

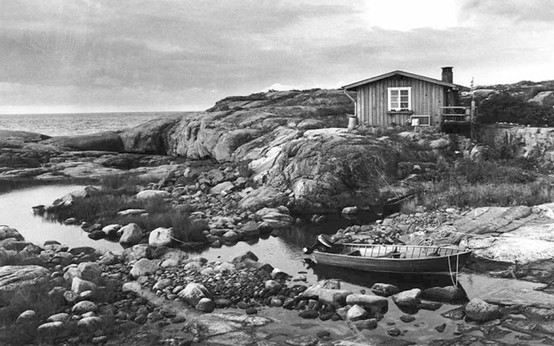

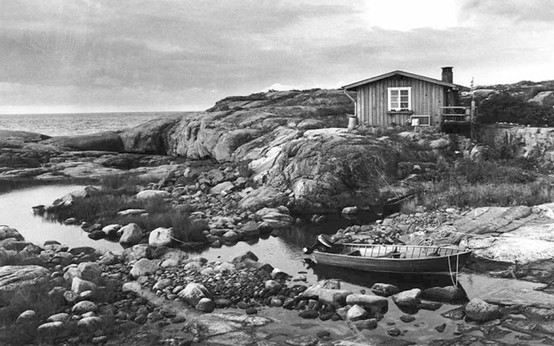

Tove Jansson’s Island

Perhaps a bit extreme, but I can see the appeal of an

‘island of one’s own’. The island is as much a character in Jansson’s books as

anyone else, if not the most enduring one.

What is interesting about all of these writing places, and

when you start reading more about writing rooms, is how many writers had sheds

or huts completely separate to their home to do their writing in. I suppose

this makes a lot of sense: going to the shed at the bottom of the garden

creates a break between home responsibility and the job of writing and in that

distance between back door and shed door the writer can emerge. Creating a

space in which you write, and only write, is something that perhaps helps to

ease the journey between the ordinary version of you and the you that creates.

It’s an interesting idea. My writing room isn’t just a writing room, it’s a

shared space in which I can write and my family can read and play games and

share quiet time with each other. It’s not perfect, but it is a lot better than

where I was before. But writing this blog has got me wondering: perhaps there

is room in my garden for a shed...?

I’ve been a little obsessed with Virginia Woolf recently.

Something happened after reading Olivia Laing’s excellent ‘To the River’ and since then I’ve found myself

wanting to know more about this woman, this writer, who seems to be remembered

more for walking into the River Ouse with her pockets weighted with stones than

for her groundbreaking fiction. I’ve also been pretty obsessed with memoirs and

personal stories, so Virginia Woolf’s diaries seemed a perfect read to me. It

was also helpful that the wonderful Persephone Books include her diaries, as edited by her husband Leonard Woolf, in

their catalogue so not only was I going to read insights from the mind of a

great writer, I also got to lend my (small) support to the independent

publishing industry. Oh, how virtuous am I?

I’ve been a little obsessed with Virginia Woolf recently.

Something happened after reading Olivia Laing’s excellent ‘To the River’ and since then I’ve found myself

wanting to know more about this woman, this writer, who seems to be remembered

more for walking into the River Ouse with her pockets weighted with stones than

for her groundbreaking fiction. I’ve also been pretty obsessed with memoirs and

personal stories, so Virginia Woolf’s diaries seemed a perfect read to me. It

was also helpful that the wonderful Persephone Books include her diaries, as edited by her husband Leonard Woolf, in

their catalogue so not only was I going to read insights from the mind of a

great writer, I also got to lend my (small) support to the independent

publishing industry. Oh, how virtuous am I?

.jpg)