You may (or may not) be aware that August is Women in

Translation month in the book reading universe (#WITmonth over on Twitter), a

movement being ably championed by Biblibio and I’d encourage you to give her blog a visit as she’s been exploring some

great writers and great books over the course of the month. When talking about

women in translation in this context, this means women writing in languages

other than English being translated into English. There are, of course, many

amazing female writers of colour writing excellent books in English (Chimamanda

Ngozi Adichie, NoViolet Bulaweyo, Xiaolu Guo, Arundhati Roy to name but a few,

more obvious examples), but given that books translated into English comprise

such a small portion of the market, and books by women translated into English

a depressingly small proportion of that, the purpose of Women in Translation

month is to spread the word about this under-represented section of the writing

world. Maybe you’ll discover a new, amazing writer in the process. Who knows?

I have made a much more conscious effort to try to read

female writers from different cultures this year and I have to say I have

discovered some amazing writers. The following represents my list of female

writers in translation that everyone should read. I am aware that this list, in

and of itself, is not hugely representative and I am no doubt missing some awesome

writers and whole cultures (for example, I have not yet had chance to explore

Middle Eastern, African, South American or non-Japanese Asian writers in any

depth. The world is large.) that I haven’t yet encountered. If you think anyone

is missing, please share your thoughts in the comments.

Without further ado, here are my suggestions.

Tove Jansson

(Finland)

What would my list of favourites be if it didn’t mention Tove Jansson? Written by

somebody else, I think. Jansson has something for everyone, from her excellent

Moomintroll books which are great for kids and adults both, to her profound and

life-affirming shorts in The Summer Book and The Winter Book. Fair Play is an

excellent exploration of interrelationships and The True Deceiver a cold and

fascinatingly odd book. Jansson’s books are full of wisdom and insight, truth

and honesty. In the words of Moomintroll:

What would my list of favourites be if it didn’t mention Tove Jansson? Written by

somebody else, I think. Jansson has something for everyone, from her excellent

Moomintroll books which are great for kids and adults both, to her profound and

life-affirming shorts in The Summer Book and The Winter Book. Fair Play is an

excellent exploration of interrelationships and The True Deceiver a cold and

fascinatingly odd book. Jansson’s books are full of wisdom and insight, truth

and honesty. In the words of Moomintroll:

“Just think, never to

be glad or disappointed. Never to like anyone and get cross at him and forgive

him. Never to sleep or feel cold, never to make a mistake and have a

stomach-ache and be cured from it, never to have a birthday party, drink beer,

and have a bad conscience…

How terrible.”

Elena Ferrante

(Italy)

I’m jumping on the bandwagon and giving a shoutout for Elena

Ferrante here, one of the most exciting writers I’ve discovered this year. Her

novel The Days of Abandonment is a wild and unsettling exploration of the

breakdown of a woman following the end of her marriage, in which the main

character is flawed, confused, angry, vulgar and a pretty terrible mother who

makes some rotten choices and does not escape unscathed. I am reliably informed that her Neapolitan

series (beginning with My Brilliant Friend) is an excellent read and I’m so

confident it is, that it’s on my ‘to buy’ and not ‘to borrow’ list.

I’m jumping on the bandwagon and giving a shoutout for Elena

Ferrante here, one of the most exciting writers I’ve discovered this year. Her

novel The Days of Abandonment is a wild and unsettling exploration of the

breakdown of a woman following the end of her marriage, in which the main

character is flawed, confused, angry, vulgar and a pretty terrible mother who

makes some rotten choices and does not escape unscathed. I am reliably informed that her Neapolitan

series (beginning with My Brilliant Friend) is an excellent read and I’m so

confident it is, that it’s on my ‘to buy’ and not ‘to borrow’ list.

Simone de Beauvoir

(France)

Most famous for her feminist tract The Second Sex and her

relationship with Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir was an intelligent and

driven woman who also wrote some amazing books. The Woman Destroyed, a triptych

of mid-length stories, blew me away the first time I read it and should be

compulsory reading for kids in their late teens as an excellent exploration of

female empowerment (or the lack of it). I certainly shall be encouraging my

kids to read it. It’s a great companion piece to Ferrante’s The Days of

Abandonment (mentioned above). De Beauvoir also wrote honestly and with

difficulty about her relationship with her mother and the expectations placed

upon her.

Most famous for her feminist tract The Second Sex and her

relationship with Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir was an intelligent and

driven woman who also wrote some amazing books. The Woman Destroyed, a triptych

of mid-length stories, blew me away the first time I read it and should be

compulsory reading for kids in their late teens as an excellent exploration of

female empowerment (or the lack of it). I certainly shall be encouraging my

kids to read it. It’s a great companion piece to Ferrante’s The Days of

Abandonment (mentioned above). De Beauvoir also wrote honestly and with

difficulty about her relationship with her mother and the expectations placed

upon her.

Fumiko Enchi (Japan)

If you’ve read this blog at all you will probably be aware

that I have a particular love for Japanese fiction. It’s worth mentioning that

the first credited novel, The Tale of Genji, is both Japanese and written by a

woman (Murasaki Shikibu) and if you read only one novel of Japanese origin,

this mighty tome is one worth selecting. But I’m not talking about Genji here

(even though I am) but the equally mighty Fumiko Enchi. Her most famous work,

The Waiting Years, is a tense and unsettling exploration of a Japanese marriage

in which the woman has been replaced by a younger (too young) concubine. Sadly

Enchi is quite difficult to get hold of in UK, but if you’re lucky and you have

a great library any of her works is worth exploring.

If you’ve read this blog at all you will probably be aware

that I have a particular love for Japanese fiction. It’s worth mentioning that

the first credited novel, The Tale of Genji, is both Japanese and written by a

woman (Murasaki Shikibu) and if you read only one novel of Japanese origin,

this mighty tome is one worth selecting. But I’m not talking about Genji here

(even though I am) but the equally mighty Fumiko Enchi. Her most famous work,

The Waiting Years, is a tense and unsettling exploration of a Japanese marriage

in which the woman has been replaced by a younger (too young) concubine. Sadly

Enchi is quite difficult to get hold of in UK, but if you’re lucky and you have

a great library any of her works is worth exploring.

Yoko Ogawa (Japan)

A more modern (and living) Japanese writer, Yoko Ogawa has a

range of interesting work out there. My first introduction to Ogawa was the

dark and disturbing The Diving Pool, followed by The Housekeeper and the

Professor which, I would have to say is not Ogawa’s usual style, is just about

one of the most uplifting books I’ve ever read. What unites them is an

intelligent style and an interesting perspective, with a definite psychological

bent.

A more modern (and living) Japanese writer, Yoko Ogawa has a

range of interesting work out there. My first introduction to Ogawa was the

dark and disturbing The Diving Pool, followed by The Housekeeper and the

Professor which, I would have to say is not Ogawa’s usual style, is just about

one of the most uplifting books I’ve ever read. What unites them is an

intelligent style and an interesting perspective, with a definite psychological

bent.

Marlen Haushofer

(Austria)

Haushofer writes books that are a continuous stream of

consciousness, which are honest and deep and complex whilst appearing

deceptively simple. Perhaps best known for her post-apocalyptic work The Wall (also a movie),

which explores the life of a woman trapped in the Austrian mountains with only

a dog, a cat and a cow for company. Something has happened to the world, but

she never does find out what it is. Instead she is left alone with her thoughts

and fears and a journal to write her thoughts in. It is an interesting work of

isolation, of the influence of society, of fear and hope. Haushofer writes

powerfully of the world whilst focusing on the seemingly domestic. She is

clever, insightful and deceptive and worthy of multiple re-reads.

Marguerite Duras

(France)

Duras wrote strange books, as anyone who has read The Sailor

from Gibraltar will know. Yet her books are intelligent and insightful, unusual

and honest. Duras has a very clean way of writing, direct and precise,

razor-like and unflinching in its gaze. Duras wrote about female sexuality,

about passion; she wrote novels, stories, plays and prose. Perhaps most famous

for writing the script to the movie Hiroshima Mon Amour.

Duras wrote strange books, as anyone who has read The Sailor

from Gibraltar will know. Yet her books are intelligent and insightful, unusual

and honest. Duras has a very clean way of writing, direct and precise,

razor-like and unflinching in its gaze. Duras wrote about female sexuality,

about passion; she wrote novels, stories, plays and prose. Perhaps most famous

for writing the script to the movie Hiroshima Mon Amour.

Isabel Allende

(Chile)

Allende is a writer I’ve only touched upon, and one that is

difficult to categorise. Known for her magical realism works like House of the

Spirits, she has also written books of historical fiction (Eva Luna), a book

about Zorro, and books for young readers (Kingdom of the Golden Dragon, which

is very entertaining). Allende writes about people, stories of passion (as she

refers to in her excellent TED talk,

which is one of my favourites) and intrigue. In her catalogue, there should be

something for everyone.

Allende is a writer I’ve only touched upon, and one that is

difficult to categorise. Known for her magical realism works like House of the

Spirits, she has also written books of historical fiction (Eva Luna), a book

about Zorro, and books for young readers (Kingdom of the Golden Dragon, which

is very entertaining). Allende writes about people, stories of passion (as she

refers to in her excellent TED talk,

which is one of my favourites) and intrigue. In her catalogue, there should be

something for everyone.

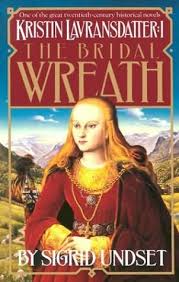

Sigrid Undset (Norway)

A Nobel Prize winner, no less. Undset is known for her epic

story Kristen Lavransdatter, which follows the life of a woman in 14th

Century Norway. Kristen makes choices for herself, based on her desires, and

has to live them out. A sinful life, as some would see it. The novel itself was

considered controversial due to its frank treatment of sex and female sexuality

and desire. It is an epic, engaging and involved story with life-filled

characters who behave frustratingly, but truly to themselves.

A Nobel Prize winner, no less. Undset is known for her epic

story Kristen Lavransdatter, which follows the life of a woman in 14th

Century Norway. Kristen makes choices for herself, based on her desires, and

has to live them out. A sinful life, as some would see it. The novel itself was

considered controversial due to its frank treatment of sex and female sexuality

and desire. It is an epic, engaging and involved story with life-filled

characters who behave frustratingly, but truly to themselves.

Adania Shibli

(Palestine)

I have read only one work by Shibli, the brief but poetic

Touch, but it was a highly effective work. Her writing is beautiful yet

powerful, she obscures her subject but reveals more by doing so. Her writing is

pure, confusing and requires more than one reading. Shibli is a poet who writes

in prose, and I can think of no better way of speaking for her than allowing

her to speak for herself:

“The written words

followed her eyes onto everything. Some books always stood between her eyes and

all other eyes in the house, always hiding its world, which, if it appeared

from time to time, appeared as a world whose words were read rather than heard,

and so she did not say anything.”

No comments:

Post a Comment